If cities are to accommodate growing populations, they must become more intelligent. By 2050, 68% of the world's population, up from 55% today, will live in urban areas, according to the United Nations. Additionally, with a predicted human population of close to 10 billion by 2050, making effective use of every square inch of city space is a top priority for local governments.

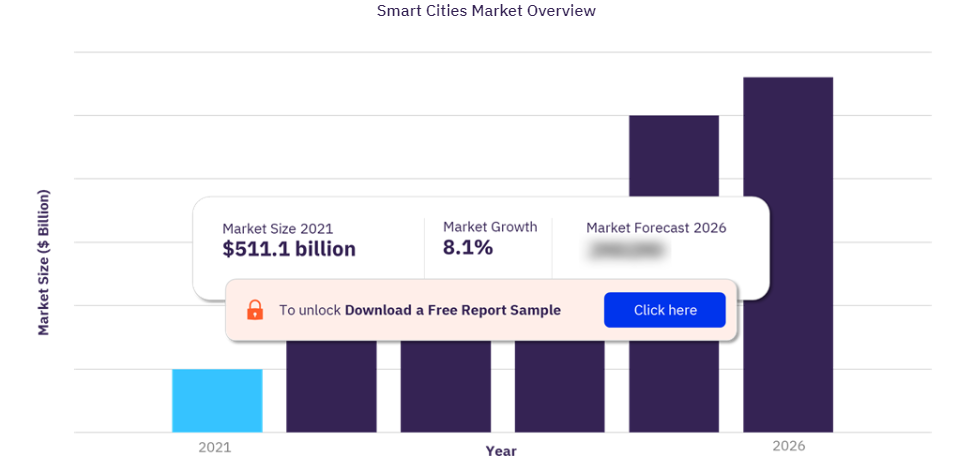

This makes for a market with worthwhile potential for the organizations giving the innovation arrangements driving the urban communities representing things to come, from shrewd waste administration to independent conveyance robots. The smart city market is expected to be worth $833 billion by 2030, up from $441 billion in 2018.

This industry has traditionally been dominated by more specialized industrial companies like Siemens, Hitachi, and General Electric. However, in search of new revenue streams, powerful tech companies operating in conventional consumer markets are increasingly expanding into industrial firms.

David Bicknell, a principal analyst on the thematic research team at GlobalData and an authority on smart cities, states, "Big Tech wouldn't be in smart cities market if it didn't see it as a money-making opportunity."

However, what tech companies see as diversification is seen by critics as a power grab in emerging markets from businesses that have been accused of slowing down competition in their own industries.

In a 2019 report on smart cities, GlobalData thematic researchers noted, "There are already fears that companies that gain an early foothold in smart cities will come to dominate so-called urban technology, just as the early days of the internet were dominated by proprietary solutions before a more open approach took over."

Alphabet, which owns Google, and Amazon, for example, are expanding into smart cities while simultaneously fighting multiple antitrust investigations on both sides of the Atlantic. Their opponents worry that they might be able to control the expanding industry thanks to their substantial data and financial resources.

Since Google owns 90% of the search engine market, it can join Facebook and Google in the digital advertising duopoly. Alphabet is currently attempting the same thing in smart cities.

Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary focused on infrastructure and urban planning, is one of the tech giant's numerous projects. By making products, investing in new businesses, and actively participating in the design of city spaces, it aims to "make cities more sustainable and affordable for all."

A smart city project, also known as Sidewalks, is in the works at e-commerce powerhouse Amazon. It creates a "neighbourhood network" based on Bluetooth Low Energy and other frequencies using selected Amazon home devices to extend internet access beyond the home.

AWS, the cloud computing powerhouse of the online retailer, is also collaborating with the City of Chicago on OpenGrid, a real-time, open-source situational awareness program designed to boost city operations' efficiency.

Data is often referred to as the new oil. Data, in contrast to oil, may have an infinite supply, which is mentioned less frequently. In theory, vendors who control that data pool could use it to gain a competitive advantage in other areas as more sensors are installed in city spaces. Amazon excels in this sector; It is accused of benefiting from its dual role as a platform for other sellers and a retailer of its own goods, using data from third parties to guide its own retail decisions, in one of its antitrust charges.

Even with anonymized datasets, a technology company might be able to gather insights that help it expand its business interests elsewhere and make it more difficult for smaller startups to enter the smart city market. Additionally, this raises concerns regarding how authoritarian regimes might use the technology to exert control over their citizens.

Reconnaissance perspective

Past the business consequences, protection campaigners have been ringing the alert over Enormous Tech's developing job in metropolitan spaces.

According to Eva Blum-Dumontent, a senior research officer at Privacy International, "we have observed the emergence of a narrative that says systematic data generation, collection, and centralisation are the answers to all problems." Companies that sell data processing and AI to local governments promote this narrative, which has resulted in the very real and tangible transformation of our cities into public spaces that are increasingly monitored as well as places of exclusion and discrimination.

Big Tech surveillance is most prevalent in China, where citizen movements are tracked by computer vision, facial recognition, and AI and fed into the SkyNet mass surveillance network. This, in turn, has a strong connection to China's Social Credit System, a government database that evaluates citizens' trustworthiness by tracking their every move and interaction throughout a city.

These security concerns are personally connected to the contribution of China's local tech monsters in metropolitan spaces. PATH, an initiative to assist 500 Chinese cities in becoming smart cities, was launched in 2018 by four Chinese tech giants: Ping An, Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei.

Alibaba's City Brain system, which makes use of artificial intelligence to manage transportation networks, is operated in Hangzhou by the e-commerce giant. It was given control of 104 traffic light intersections in the Xiashoshan district of the city, and in its first year, its algorithms were able to improve traffic efficiency by 15%.

The software is provided by Alibaba Cloud, but the data belong to the city. However, the relationship between Big Tech and Big Government is further questioned when the state is authoritarian.

The tangled relationship has taken center stage for the Chinese telecom giant Huawei. It is one of the leading suppliers of equipment for 4G and 5G, making it one of the biggest tech players in China. Prior to a few years ago, its global spread appeared to be unstoppable. In 2019, when questions about Huawei's ties to the Chinese government reached boiling point, that growth began to unravel.

Critics cited the company's state subsidies, its founder's history in the Chinese military, and a Chinese national security law that could theoretically compel the company to grant the government access to communications on its network. Huawei has repeatedly refuted claims that it poses a threat to national security. The company was ostracized across the West despite the lack of a smoking gun. Most importantly, the saga emphasized Western governments' admission of the critical role tech companies play in city infrastructure and the potential risks they could pose, whether real or imagined.

Zero privacy, smart city?

China is not the only country with smart city surveillance. In 2019, developers in King's Cross, London, sparked outrage when it became clear that CCTV cameras with live facial recognition were monitoring people passing by. An investigation by the UK's data regulator was prompted by the system's secret installation and lack of police oversight.

While the live facial acknowledgment programming was not given by Huge Tech, such organizations are giving observation frameworks somewhere else. Amazon's Ring camera system has partnered with over 2,000 US police and fire departments, effectively transforming a consumer camera into an extension of a state surveillance network, all made possible by Big Tech. As part of a partnership with the British police, Amazon has given away thousands of free Ring devices.

The relationship that Amazon has with law enforcement extends beyond hardware. Rekognition, its facial recognition software, was sold to US law enforcement and is based on AWS technology. In June 2020 it put a one-year ban on offering Rekognition to police after common freedom bunches raised worries about the tech's possible racial predisposition. IBM also stopped selling its own facial recognition software to police because of the same pressures.

These responses, in addition to protesters tearing down smart streetlights in Hong Kong, demonstrate a strong opposition to smart city technology when citizens believe it poses more risks than benefits. However, one incident has emerged as an illustration of the backlash against Big Tech in smart cities.

Unintelligent city: The Sidewalk saga: Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Google co-founder Eric Schmidt defended the Quayside project in Toronto as a community built "from the internet up."

It was first proposed as a 12-acre neighborhood in October 2017 with the goal of becoming a truly smart city with features like "snow-melting roadways," an "underground delivery system," and homes with cutting-edge wood-frame towers to make housing more affordable. However, the project fell apart over the next two years. First, when Sidewalk Labs expanded the neighborhood to 190 acres, tensions rose. The Google company and Waterfront Toronto, the organization in charge of the renovation, also had visionary disagreements. Residents, on the other hand, expressed the greatest opposition because they were concerned that the tech giant would acquire and store their personal information.

Roger McNamee, a venture capitalist at the time, wrote in a letter to the Toronto city council, "The value to Toronto cannot possibly approach the value your city is giving up." A vision of a dystopian future is out of place in a democratic society.

Notwithstanding guarantees by Google that resident information wouldn't be imparted to outsiders, the backfire proceeded.

The uncertainty surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic was cited as a reason for the project's termination in May 2020. However, GlobalData's Bicknell claims that "data privacy" was the primary cause of its demise. He adds that the incident may also have broader repercussions for smart city projects.

He elaborates, "The failure of that project overshadows other good smart city engagements." It was a project with a lot of attention, and citizens and other cities will share the concerns about data privacy.

Big tech's role in smart cities seems unlikely to diminish. Smart cities benefit everyone. Therefore, how can it be ensured that it serves citizens rather than Big Tech's financial interests?

To begin, it is important to point out that not all smart city projects present immediate dangers, whether they are related to market dominance or data privacy. For instance, Vodafone and SES Water collaborated last year to install narrowband IoT sensors in water pipes to detect leaks by monitoring pressure, flow, temperature, and acoustic signals. Residents are unlikely to object to the project's goal of reducing water leakage by 15% in five years, which could save billions of liters of water per day.

The management of city spaces will be crucial in countries' efforts to recover from the pandemic in order to strike a balance between safety and normalcy. Technology for smart cities could be a part of that solution, but GlobalData's Bicknell says that Big Tech should be careful with their involvement.

He elaborates, "Maybe cities just need to be resilient rather than smart for the time being." Big technology can aid. It has the potential to transform thinking, scale, and concepts. It can't be seen as a massive organization that is overshadowing projects, as might have happened in Toronto. Big technology was not the answer. That was the issue.

According to Justin Bean, Hitachi Vantara's global director of smart cities and smart spaces, there is clearly a "gap in trust between citizens, business, and government."

He believes that demonstrating the advantages to the local community and society as a whole from the beginning is essential to the success of smart cities.

According to him, "this means clearly defining the goals and objectives that will be achieved through the deployment of technology or digital solutions." Additionally, we must collaborate to raise public awareness and encourage citizen participation because, ultimately, solutions must be developed with the concerns of citizens in mind first and foremost. Collaboration is required.

He adds that the "onus is on organizations and legislatures to guarantee that any resident information protection concerns are tended to in a straightforward way".

Implementing specific smart city laws and regulations is yet another strategy for mitigating the dangers posed by Big Tech in urban areas. However, this could be a challenge, as GlobalData analysts noted in a 2019 smart cities report: Local laws will be different for each problem being solved in different cultures and geopolitical locations.

Keeping the general public informed is essential, according to Blum-Dumontent of Privacy International.

“It is essential that smart city projects take place after extensive public input sessions to ensure that they meet the needs of the public. She added, "One of the most important aspects is transparency as well as data minimization."

Bicknell concurs that one of the most effective strategies for controlling Big Tech's role in smart cities is transparency. He focuses to the Shrewd Urban communities Challenge in Canada, which constrained organizations to unveil their applications by means of a metropolitan site.

According to Bicknell, "that created a more open process and generated less suspicion of Big Tech motives." A little self-control and an openness to receiving criticism would be helpful.

"Maybe Big Tech should behave a little bit more like Small Tech."